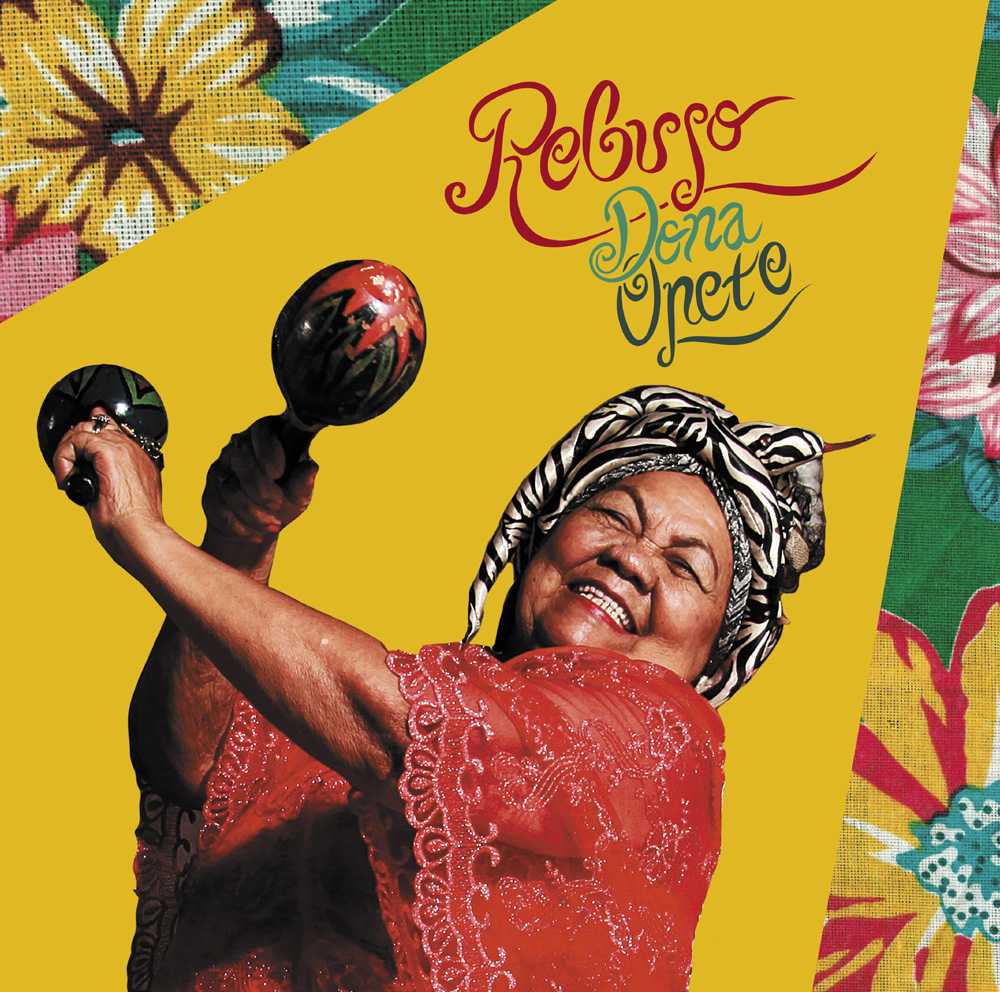

On the eve of her 80th birthday, Dona Onete – ‘the grande dame of Amazonian song’ – returns with Rebujo, a love letter to her hometown of Belém, situated deep in the Amazon.

Rebujo brims with two music styles born in Belém: carimbós, influenced by African grooves, and bangues, a ska-type rhythm, plus there’s a cumbia, brega (‘romantic’ music) and samba.

“I love her and her band“ David Byrne “One of the best shows I have seen” Gilles Peterson

“I dedicate this album to the culture of my region” Dona Onete

Whilst the Brazilian government turns its back on Brazil’s minorities, Onete embraces diversity – especially in her state of Pará – which she believes “with its mix of colours, rhythms, flavours, is the most diverse in Brazil”. A former teacher, political activist and culture minister, Dona Onete began a career in music a decade after she’d officially ‘retired’, first turning people on with her saucy lyricism and kiss and tell aged 73: “Searching for my mouth, giving me a wet kiss, I embrace your sweaty body” (Acão e Reacão).

Since her previous album Banzeiro, Onete’s reputation has flourished in Brazil. She performs the length and breadth of the country to predominantly young and switched on audiences. She’s composed and sung the theme song for one of Brazil’s leading soap operas (A Força do Querer) and been awarded the Brazilian Ordem do Mérito Cultural in recognition for her contribution to Brazilian culture. She plays benefit shows for endangered Amazonian tribes and Na Linha Do Arco-íris (The arch of the rainbow) from Banzeiro, telling the story of a gay friend’s murder, is now an LGBT anthem.

Outside of Brazil, she has been invited to perform at Roskilde, Womad (UK, NZ & AUS), Gilles Peterson’s Worldwide Festival and TFF Rudolstadt amongst other festivals and her video for previous single No Meio do Pitiú has over 9 million views on Youtube. She’s a spokesperson for indigenous people and minorities and on a recent trip to Australia she called out the government’s treatment of Aboriginal people live on ABC news.

Whether composing songs praising 19th century Brazilian revolutionaries (Fogo na Aldeia), beautiful black women from the favela (Musa da Babilonia) or the racial mix in Belém, “My love is black… blonde…. dark… creole… mulatto… Caboclo (a mix of native Indian and European)” (Mistura Pai D’Égua), Rebujo is part love-letter, part war-cry: “We’re messed up, I can see that we’re divided. I want us to be united… I’m dedicated to fight for my culture.”

The album’s Amazonian references are resplendent: flesh-eating piranha (Festa do Tubarão), mango-scented ticks (Vem Chamegar), biting tucandeira ants (Balanço do Açaí), African gods such as Borocô (Tambor do Norte) and banho de cheiro: a herbal bath used to ward off evil spirits (Mistura Pai D’Égua). The title Rebujo is the name for the turbulence in a river created as currents pass through: it’s the rebujo that lifts silt and detritus from the riverbed giving the Amazon its muddy colour – and making the waters perilous for swimmers.

Dona Onete produced Rebujo with long-time collaborator Pio Lobato – one of Brazil’s most respected guitarists and an expert in the Amazonian-surf guitar style guittarada. Lobato’s wavy guitar lines run like fishing lines throughout the album, catching Breno Oliveira’s bouncing bass, Marcos Sarrazin’s leaping sax and the pulsating rhythms from drummer Vovô Batera and percussionist JP Cavalcante.

Onete was born in 1938 on Marajó, the world’s largest river island situated in the mouth of the Amazon. Her mother was indigenous Amazonian whilst her father was descended from African slaves; he died soon after she was born and her mother passed away when she was nine, Onete then being cared for by her grandmother. Her family moved to Belém when she was a child yet she regularly visited Marajó: “One of my biggest musical influences are Marajoara, local cowboys who improvise songs. They turn common phrases into beautiful poetry and whenever I write a song, I remember them”. By the age of 15 she was singing in bars and cowboy festivals, yet her musical ambitions were soon crushed: “I was married at 22 and when I tried to sing at home my husband didn’t like it so I had to stop”.

She became an ardent researcher of the rhythms, dances and traditions of the Amazon’s indigenous people. In the early Eighties Onete quit teaching and became a civil servant – yet also a campaigner for workers’ rights, an experience that “changed her life”. “The government sent me on a civil defence course – yet it led me to become a political activist. I understood the problems caused by politicians and those with power, and learnt how to fight against injustice. I decided to use what I learnt to defend my people, not for the benefit of the government”. Following her retirement in 1990 she became her region’s secretary of culture from 1993-1996. “I helped local musicians and local culture that people didn’t value. I have the chance to help Amazonian communities through my music so I cannot just sing and close my eyes to the people’s plight.”

In the early 2000s Onete’s second husband supported her musical ambitions and it was whilst singing at a friend’s party in 2006 that a local band overheard her. Initially rejecting their offer to sing with them, she was eventually persuaded and soon became a local celebrity known for her risqué lyrics. A debut album, Feitiço Caboclo, soon followed and her contemporary take on the music of Pará was a critical success with Onete touring Brazil playing to crowds of thousands. 2017’s Banzeiro continued her ascendency internationally.

“My energy comes from the river” she says “It’s like blood rushing through my veins, there’s no stopping it – or me”

Duncan Ballantyne