The award-winning Israeli-Persian singer returns with “Roya” (fantasy in Farsi) an exhilarating blend of tradi-modern rhythms and retro-Persian sonics. Recorded in secrecy in Istanbul with her band from Tel Aviv and risk-defying Iranian musicians from Tehran. A musical portal to a place of peace, joy and unfettered freedom.

Shadow patterns through a decorative screen window. A door opening deep inside a deserted ancient palace. A shimmering blue veil through which kohl-rimmed eyes watch, and widen. Intrigue. Mystery. The past and present, overlapping. Roya.

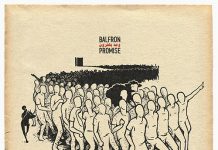

The new third album from award-winning Israeli-Persian singer Liraz is an invitation to dream. Anthems, love ballads, glittery Middle Eastern dance tunes … A collection of 11 tracks that enrich that signature blend of tradi-modern rhythms and retro-Persian sonics, Roya (‘fantasy’ in Farsi) is music as a magic portal, an arched gateway to a place of peace, joy and unfettered, chador-waving freedom.

“My fantasy, I wished for peace in the world,” she sings in Farsi, in that golden voice, on the hallucinogenic title track. “I will not lose my hope/You’ll see, our hearts will cross.”

Liraz and her Israeli sextet (three women, three men) recorded Roya over ten days in Istanbul, in a basement studio hidden from public view and crackling with creativity.

With them, on violin, viola and the tar, the wasp-waisted wooden Iranian lute, were composers and musicians from the Iranian capital, Tehran. The same clutch of anonymous players who previously collaborated with Liraz online, no questions asked, no faces shown, under the radar of Tehran’s secret police, for her feted 2020 album, Zan. Players who’d travelled undercover from Tehran to Istanbul to work with Liraz and producer/multi- instrumentalist Uri Brauner Kinrot in the flesh.

Or at least, that is what Liraz imagined.

‘There is a passage connecting our tongue and heart, sustaining the secrets of the world and soul,’ wrote Rumi, the greatest Sufi mystic and poet in the Persian language, whose prose Liraz treasures. ‘As long as our tongue is locked the channel is open/the moment our tongue unlocks the passage will close.’

“Was it just in my mind? Was I really in the same room as these Iranian soul sisters and brothers?” Liraz pauses, waves an elegant hand. “All I remember are fragments: the fear and anxiety I felt when I knew they were on their way. The tears of joy and relief we all cried as we embraced. And the music we made! Such music!” She flashes a smile. “It just poured out of us,” she says.

With strings snaking through pulsing electronics and wah-wah-guitars, ‘Azizam’ is a psychedelic wonder, strobing around lyrics that tell of unhinged obsession (“You are the evil killing me/I, who is in love with you”). Featuring music written by bassist Amir Sadot, ‘Doone Doone’ is a rollicking ode to the Tehrani musicians Liraz befriended through computer screens – and who might have been right there, in touching distance, recording with her. ‘Mimiram’ delivers dramatic protestations of love with knowing irreverence; while ‘Omid’ – [which is both a man’s name and the Farsi word for ‘hope’] with lyrics by an anonymous Iranian female musician and music by Zan co-writer Ilan Smilan – tells of a man named Hope and of hope, who is also a man.

A slow, lonely song about Iran, the string-and-synth-driven ‘Tanha’ was recorded on the day the Iranians may or may not have arrived in Istanbul. “I am singing about the boundaries that have melted between us,” says Liraz, who wrote the words and co-wrote the music with Smilan and Brauner Kinrot. “I cried a lot between takes.”

Her Hebrew accent intact (“This is my story, my culture clash”), her confidence boosted by prestigious awards (she was Songlines Artist of the Year 2021) and widespread international acclaim, Liraz has never sounded so passionate, so strong and defiant. Roya, then, is the next phase of a high-profile career further distinguished by a drive to fight oppression, to champion the right of women everywhere to sing, perform and be heard.

“Israel and Iran are not living in peace. Israelis cannot visit Iran, and Iranians cannot visit Israel. If Iranians contact Israelis they will go to jail,” says Liraz, whose parents, Sephardic Jews of Iranian–Jewish descent, left for Israel back when the two countries had close ties – but when, even prior to the 1979 Islamic Revolution, being a Jew in Iran was kept quiet.

Her grandmother had wanted a career as a singer, a profession forbidden to women in Iran.

“Even aged 85, she is a great singer; the other day I put on a record by an Iranian singer and she got up and sang loudly. My family have to sing,” says Liraz, who grew up dancing to the music of divas such as Ramesh and Googoosh celebrated in Tehran in the ‘60s and ‘70s, the golden age of Persian pop. She also loved female singer-songwriters: Kate Bush, Tori Amos.

Lessons in singing, music and acting – and a stint spent clubbing – were followed by three years working in the US as an actress, appearing in the big budget films such as Fair Game and A Late Quartet. In Tehrangeles – the Little Tehran of Los Angeles – she found her people, embraced her inner Persian: “Iran has always seemed like a lover I’ve been longing for. I can sense how it is to be Iranian but I’m not in that bubble inside Iran.”

“This paradox made me a dreamer,” Liraz continues, who in a neat art/life twist appeared as a Farsi-speaking Mossad operative in the 2020 Apple TV espionage series Tehran. “What if I was born in Iran and could not sing – would I try and escape? There are always so many stories and visions inside my head. But I know that I need to sing, I must sing, for the muted women of Iran. And I want to sing to Iran about my feelings for Iran.”

Her 2018 debut album Naz, a collection of mainly pre-revolutionary pop songs by her favourite female Iranian singers, lit up Iran’s social media. Liraz was sent videos of women dancing inside their homes, their chadors, headscarves and veils cast off, their faces joyous. Iranian musicians began sending her clips, lyrics and melodies via encrypted files, and so the songs for Zan – and her relationships with the anonymous musicians – took shape.

With each album, Liraz has grown bolder, more outspoken (ask her about Palestine and she’ll extol Palestinian rights, too). If recording in an underground studio with the musicians from Tehran was a fantasy, it was a palpable one. The scintillating ‘Bishtar Behand’ captures the healing power of laughter and togetherness. ‘Gandomi’, its lyrics and music written anonymously, praises cross-cultural romance and commitment; where ‘Joonyani’ tells of crazy love, of kissing pictures each night, the cinematic ‘Bi Hava’ – string-laden and serene – seems to close the circle of friendship between Liraz, her band and the Tehrani musicians.

“I sing that it is not one day we are going to meet. We are already here with each other, in the now. So let us enjoy being together.”

On the closing track, a female-led version of the opener ‘Roya’, they do precisely that. “I’d felt so much power from these ladies who arrived from Iran,” says Liraz. “We became like sisters. On the last day, with one hour left before everyone had to go, I asked the Iranian women and the three women in my band to record a very live organic fusion of ‘Roya’.”

“We got it in one amazing take. We all cried as we hugged and said goodbye and then just like that, everyone was gone.” Her dark eyes flash. “Like they’d never been there at all.”

Somewhere in the past, fluttering towards the future, a blue veil flies, free, in the wind.

Glitterbeat Reacords and NMR (photo: Shai Franco, Cem Gültepe