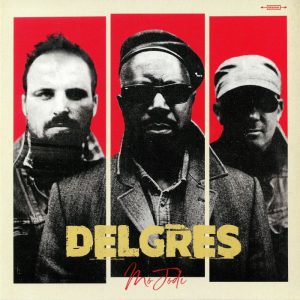

DELGRES – MO JODI (JAZZ VILLAGE 2018)

DELGRES – MO JODI (JAZZ VILLAGE 2018)

Born in the suburbs of Paris from immigrant parents, Danaë, 53, was exposed to a great variety of music from a young age. “We were listening to lot of Cuban music, salsa, beguine, Haitian konpa and African music,” he says, recalling the sounds at home. “My bigger sisters listened to James Brown and old-time R&B … And my godfather was crazy about English rock! I can still picture the compilation he brought home with The Kinks, Rolling Stones and Beatles. That British sound is part of who I am.” Jazz was also a substantial influence — Herbie Hancock’s jazz-rock, Charlie Parker’s bebop and the great jazz guitarists Wes Montgomery, Charlie Christian and George Benson.

Born in the suburbs of Paris from immigrant parents, Danaë, 53, was exposed to a great variety of music from a young age. “We were listening to lot of Cuban music, salsa, beguine, Haitian konpa and African music,” he says, recalling the sounds at home. “My bigger sisters listened to James Brown and old-time R&B … And my godfather was crazy about English rock! I can still picture the compilation he brought home with The Kinks, Rolling Stones and Beatles. That British sound is part of who I am.” Jazz was also a substantial influence — Herbie Hancock’s jazz-rock, Charlie Parker’s bebop and the great jazz guitarists Wes Montgomery, Charlie Christian and George Benson.

He got his first guitar at 15, a gift from a brother-in-law to “ just pass the time in the summer,” but went on to build a remarkable career in music, first by playing jazz and fusion around Paris clubs, later as a session musician, working with artists such as Peter Gabriel, Youssou N’Dour, Souad Massi, Harry Belafonte, Mayra Andrade, and Gilberto Gil.

He moved to London in 1997, following his British blues-rock dreams, and it was a defining experience. “In English clubs, people play like a smack in the face,” he says. “I learned to be fearless there, and go out like a pitbull and play it that way.” (It was also during that time that he befriended Skye Edwards, vocalist and founding member of the English electronic band Morcheeba. She joins Danaë on “Séré mwen pli fo”.

Back in Paris, he recorded London > Paris (2007), a “postcard,” as he calls it, of his eight years in the UK. And in 2015, he won Best World Music album at the Victoires de la Musique (the French Grammy), with the self-titled debut of his Afro-Brazilian project, Rivière Noire.

Curiously, it was while living in Amsterdam, where he spent three years before moving back to Paris, that he found a Dobro, a resonator guitar with a distinct sound that completed his musical puzzle.

“You have to let it resonate, and stop and listen to it, and so you start listening to yourself,” he says. “It was like learning to walk again. The songs came one by one, really listening to my deep feeling, and not caring about where it would go. I wasn’t trying to write an album. I went back to singing in Creole, like my ancestors had in Guadeloupe. I went down to the bottom. And when I opened my eyes, I had a few songs. Then I waited a long time before I put it out there. I wanted to make sure.”

For his vision of French/Caribbean/Mississippi blues, Danaë called on the kinetic drummer Baptiste Brondy, a bandmate from Rivière Noire; and to anchor the trio, in a nod to New Orleans brass bands, the Paris Conservatory-trained Rafgee, (aka Raphaël Gouthiere) on sousaphone. “For bass, I wanted something very basic, street-like, but with the ability to also be very emotional,” he explained. “You can play beautiful melodies — and you can also growl.” The CD opens with “Respecté Nou” (Respect Us), a song Danaë relates to his great-great-grandmother’s letter of freedom. “The whole Delgres project helps me really put my finger where things are sore. I’m not blaming anybody else. That just creates more hate. You have to find the strength to go out and be positive as you find your place in this world. ‘Respecté Nou’ is about that.”

“The Promise” (a snippet from a Lyndon Johnson speech) serves as prelude for the pointed “Mr. President”(sung in Creole, the lyrics say “Mr. President, you are so smart/ …/ me, I don’t know shit I’m just a musician/All I can do is sing/But I did vote for you, put my trust in your hands/ Now could you please explain what you gonna do for me?/Cause I’m still struggling, struggling, struggling”)

But then, Mo Jodi ends on an introspective note with “Pardone Mwen,” (Forgive Me) in which Danaë speaks to his sister. “In this song I ask my big sister for forgiveness, because in my family she’s been taking care of everybody, while I’ve been playing music round the world,” he explains.

“As much as we stand for freedom and information and the big principles of life, on some songs I like to take it back to the personal but it’s important for us to keep it at a pretty light level,” said Danaë. “People come to our concerts to have a good time. We share a good time, it’s not a history book.”

Sarah Folger + NMR